Introduction: The Left Shift – An Ambition Yet to Be Realised

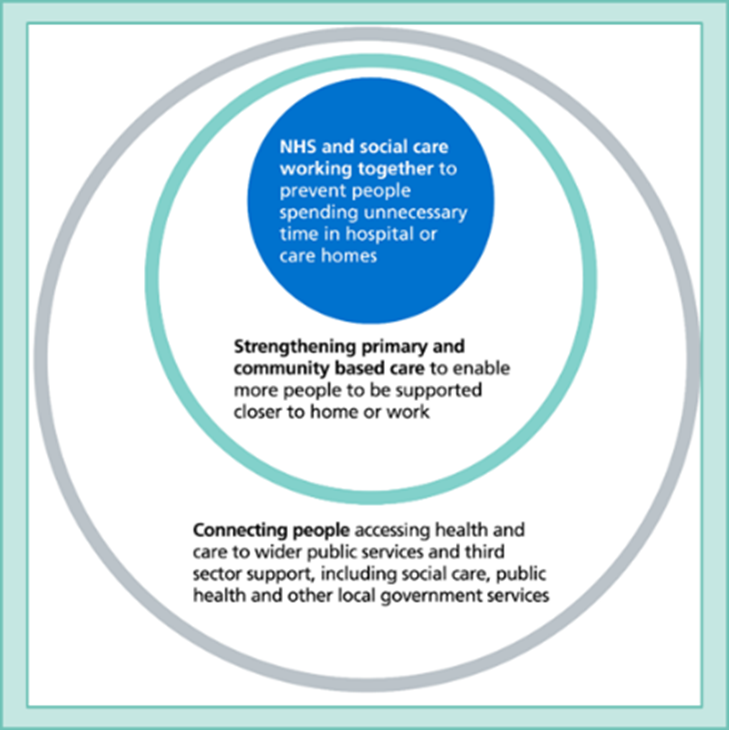

The ambition to shift care out of hospitals and into the community is not new. Lord Darzi’s Review (2024) and the government’s three strategic shifts (figure 1) outline a framework for achieving it. Yet, despite multiple past policies, the NHS has failed to deliver on these ambitions, instead prioritising acute hospital funding over long-term investment in community-based care and prevention.

Figure 1: The UK government’s three strategic shifts

This time, despite being the main beneficiary of Rachel Reeves’ first budget, financial constraints are tighter, and reforms must be linked to improved efficiency and system-wide transformation, making these shifts even harder to deliver.

While everyone agrees on the need for reform, the challenge lies in execution. How can the NHS finally turn this ambition into reality?

The Case for Prevention and Community Investment

By 2050, one in four people in the UK will be over 65, and the proportion of the population living with multiple long-term conditions (MLTCs) is rising rapidly. At the same time, weak economic growth, a failure to decommission outdated services, and a growing number of people unable to work due to long-term sickness are placing significant strain on health and care services.

As demand for hospital beds, GP appointments, and social care services rises, financial pressures make it impossible for the NHS to expand capacity at the same rate. Without intervention, the combined challenges of an ageing population and the economic burden of MLTCs will continue to rise, placing even greater pressure on the NHS.

Another important point is that health outcomes vary dramatically based on socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and geography. Life expectancy can differ by more than a decade between the wealthiest and poorest areas, and people in the most deprived communities develop multiple long-term conditions (LTCs) 10–15 years earlier than those in wealthier areas.

The current acute-focused model does little to address these disparities. By the time many patients seek care, conditions have already worsened, leading to more costly interventions, worse outcomes, and avoidable hospital admissions. A prevention-first, community-based model offers a direct solution by:

- Targeting high-risk groups with earlier intervention

- Improving long-term condition management

- Bridging healthcare access gaps

The benefits of prevention and community-based care extend beyond better patient outcomes – with increasing evidence that they also drive significant cost savings and economic returns. Research from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change has found that a 20% reduction in major chronic diseases could boost UK GDP by £19.8 billion within five years and £26.3 billion within ten years.

Similarly, analysis by NHS Confederation found that investing in community and primary care could generate up to £14 in economic return for every £1 spent, exceeding the returns from investment in acute care. This suggests that strategically investing in these care services will achieve the greatest economic impact. However, it is important to recognise that prevention-based interventions often take longer periods of time to see a return on investment (ROI).

Neighbourhood-based Care Model: The Foundation of the Left Shift

To make prevention a reality, the NHS must ensure localised, data-driven services. This is where the integration of neighbourhood-based care models and Population Health Management (PHM) becomes essential. To operationalise this shift, NHS England has published the Neighbourhood Health Guidelines (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The aims for all Neighbourhoods over the next 5 to 10 years (NHS England, 2025)

The guidelines aim to help deliver joined-up care across primary, community, and social care at a local level, ensuring that services reflect the health needs of their populations, leading to:

- More personalised care – Teams can respond to population-specific health challenges.

- Reduced acute hospital demand – Prevent unnecessary hospital admissions and reduce pressure on GPs.

- More efficient use of resources – Reduce duplication and improve care coordination.

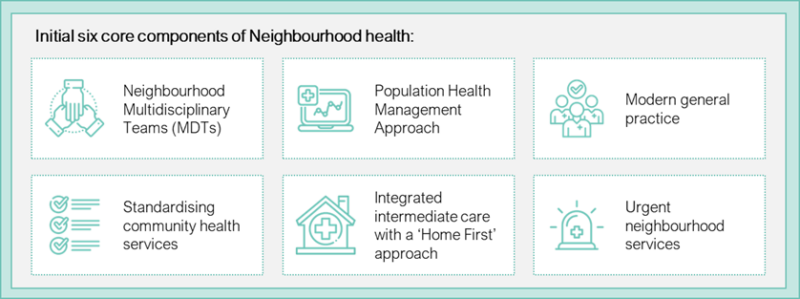

The foundations of a neighbourhood-based care model are not new, with the six core components (figure 3) already in place in some areas across the country.

Figure 3: The initial six core components of the neighbourhood-based care model (NHS England, 2025)

A key aspect of this guidance is its emphasis on both innovative care models and the strengthening of core community-based services, particularly primary and community care, which have lacked the necessary investment over the past few decades despite being the foundation of local care delivery.

Population Health Management: The Intelligence Behind the Left Shift

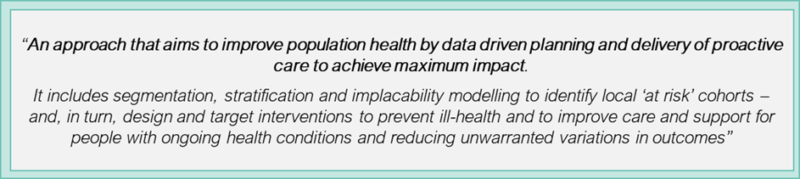

One of the critical enablers of the left shift is the integration of PHM within neighbourhood-based care models. The King’s Fund defines PHM as:

Figure 4: The King’s Funds PHM definition

PHM is the engine that enables neighbourhood-based care models to deliver targeted, proactive, and cost-effective interventions. By defining and segmenting populations, PHM allows ICSs to allocate resources where they will have the greatest impact, rather than simply reacting to demand.

Yet, one of the greatest barriers to shifting care out of hospitals is misaligned resource allocation. Historically, NHS funding has prioritised hospital-based care rather than prevention, often overlooking high-risk groups who do not actively engage with healthcare services.

This shortcoming was starkly exposed during COVID-19, when previously ‘invisible’ marginalised populations emerged with significant unmet health needs. Without robust PHM tools, the NHS struggles to anticipate these needs, leaving many communities vulnerable to avoidable health crises.

Harnessing Data for Smarter Prevention: The Role of PHM in the Left Shift

To address these gaps, Akeso has developed a PHM tool that moves beyond traditional service-user data by integrating NHS datasets with national socioeconomic and demographic intelligence from sources (e.g., ONS). This approach allows ICSs to see the full population, rather than just those actively engaging with healthcare services.

By leveraging this intelligence, ICSs can:

- Identify hidden high-risk groups before they require urgent intervention.

- Target preventative measures such as virtual wards, diagnostic hubs, or enhanced community services.

- Shift from a reactive to a proactive model.

- Optimise workforce planning by aligning service delivery with actual population health needs.

- Improve allocative efficiency, ensuring funding follows patient need.

However, the success of PHM-driven care models depends not only on advanced analytics but also on workforce capacity.

Workforce Readiness: The Missing Link in the Left Shift

While PHM-driven insights are critical, realising their full benefits depends on workforce capacity and skills. Prevention-focused care demands greater investment in key roles, including:

- Care coordinators – Ensuring patients receive the right interventions at the right time.

- Social prescribers – Addressing the social determinants of health through non-clinical support.

- Specialist community nurses and allied health professionals – Managing LTCs outside hospital settings.

These roles are crucial to reducing hospital admissions, yet remain historically underfunded. Without sufficient workforce capacity, ICSs will struggle to act on PHM insights, leaving hospital admissions unchanged and long-term health outcomes unimproved.

Neighbourhood MDTs are instrumental in translating PHM insights into real-world care. By embedding PHM within neighbourhood-based models, ICBs can create a fully integrated, proactive, and financially sustainable healthcare system.

For the left shift to become reality, the NHS must align financial incentives, workforce investment, and digital infrastructure with PHM-driven neighbourhood care. Only then can the NHS transition from reactive crisis management to a prevention-first model that delivers better outcomes for all.

The Ambition vs. Reality of the Left Shift

Despite the promising evidence and the NHS’s ambition, delivering a left shift at scale faces significant policy and systemic barriers. These include:

- Funding misalignment in the health system: Historically, budgets and payment models have incentivised hospital activity, so shifting investment into the community means lost revenue for acute hospitals. While investment in community services delivers significant long-term benefits, the urgency of acute pressures, makes it difficult to justify diverting funds away.

- Structural power imbalances: Acute hospitals historically hold more influence across the system than community and primary care providers, making it harder for these providers to secure adequate resources.

- Siloed nature of budgets for health vs. social care: Shifting care out of acute hospitals requires joined-up community health services and social care. Without aligned budgets, shared incentives, and joint commissioning, social care and health teams struggle to coordinate care leading to delays and inefficiencies.

- Lack of decommissioning outdated services: While ICBs often focus on introducing new innovations, an equally important, yet frequently overlooked, aspect is de-commissioning outdated services. Unlike introducing a new service, removing or reducing existing ones can be made difficult due to cultural resistance, public perception, regulatory challenges and the lack of incentives.

The Case for Allocative Efficiency: Shifting Resources to Where They Matter

For the left shift to happen, the NHS needs to prioritise allocative efficiency – ensuring that healthcare funds are directed where they deliver the greatest long-term impact. This often means shifting investment from acute care to upstream, prevention-focused interventions.

A key approach to improving allocative efficiency is programme budgeting, which allows funding to be allocated by major conditions rather than individual institutions. The Health Economics Unit advocates for this more flexible, targeted resource allocation model. This would ensure that funding follows patient need rather than legacy structures, creating a more integrated and patient-centred approach.

For these changes to be realised, funding mechanisms must evolve to incentivise prevention-based care. The Hewitt Review has emphasised the need for ICBs to have greater autonomy in financial decision-making, enabling a shift away from activity-based funding that favours acute hospital care. Likewise, the NHS Payment Scheme’s shift towards blended payment models offers an opportunity to embed financial structures that reward early intervention and integrated care. Aligning these policy levers with PHM-led resource allocation will be crucial in ensuring that investment follows health needs rather than institutional legacy.

Evidence from real-world examples demonstrates how this can work in practice:

- In a project between five ICBs and the Health Economics Unit, COPD funding was reallocated from acute hospital care to community-based management, leading to improved patient outcomes and reduced hospital admissions.

- Similarly, New Zealand’s Canterbury health system successfully shifted resources from hospitals to primary and community services as part of its Vision 2020 reform. Over five years, Canterbury significantly reduced acute hospital spend in favour of community care, leading to better financial control and improved health outcomes.

The Way Forward: What Needs to Change

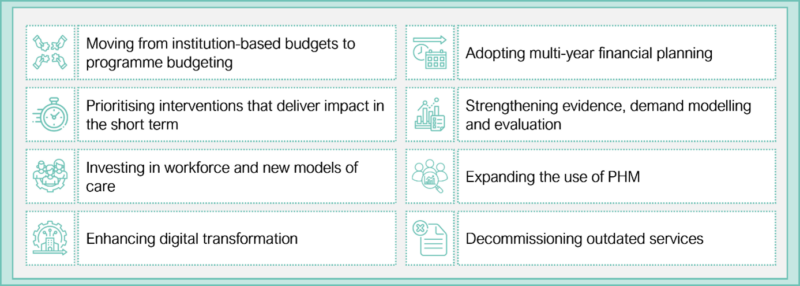

To successfully shift care into the community and prioritise prevention, the NHS must overcome systemic barriers and embed reforms that support a financially sustainable, proactive health system. The following changes will be important:

Figure 5: What needs to change

- Moving from institution-based budgets to programme budgeting: Funding should be allocated based on major conditions rather than individual organisations, ensuring that investment follows patient need.

- Adopting multi-year financial planning: ICBs need multi-year budgets that allow for sustained investment in prevention, workforce expansion, and digital transformation.

- Prioritising interventions that deliver impact in the short term: ICBs must prioritise interventions that show measurable short-term impact while building towards sustainable change. Scalable, high-impact initiatives should be prioritised to demonstrate quick wins.

- Investing in workforce and new models of care: The NHS must expand key community-based roles and ensure neighbourhood-based care models are properly resourced.

- Strengthening evidence, demand modelling and evaluation: ICBs must quantify the impact of community-based interventions, through improved impact modelling, better evaluation frameworks and financial planning that accounts for ROI.

- Expanding the use of PHM: PHM must be embedded as a core function within ICSs to identify at-risk populations early, predict future healthcare needs and allocated resources based on actual population needs.

- Enhancing digital transformation: Digital tools should be strategically deployed to streamline workflows, reduce admin, and show a clear ROI. Frontline staff must be engaged in co-designing, whilst PHM relies on data sharing, integration and interoperability, which require investment in digital infrastructure and governance.

- Decommissioning outdated services: Proactively phase out services that no longer deliver optimal outcomes. However, the NHS must provide clear incentives, support, and governance to ensure services are replaced with more effective alternatives.

Conclusion

The Darzi Review and the government’s three strategic shifts provide a framework, but systemic barriers continue to hold back progress. By investing in primary and community care through multiyear funding models, prioritising interventions which show short term ROI and impact, expanding PHM and prioritising allocative efficiency, the NHS can move beyond crisis management and build a sustainable health system for the future.

References

- Independent investigation of the NHS in England – GOV.UK

- Road to recovery: the government’s 2025 mandate to NHS England – GOV.UK

- New funding to fix the NHS: here’s how it will be spent – GOV.UK

- NHS financial sustainability

- NHS England » 2025/26 priorities and operational planning guidance

- Living longer and old-age dependency – what does the future hold? – Office for National Statistics

- Making sense of the evidence: Multiple long-term conditions (multimorbidity) – NIHR Evidence

- “Should it stay or should it go?” Making space for innovation: De-implementing old ways of working

- Rising ill-health and economic inactivity because of long-term sickness, UK – Office for National Statistics

- Trends in life expectancy in the most and least deprived areas | The Health Foundation

- Multiple conditions and health inequalities: addressing the challenge with research

- Creating better health value | NHS Confederation

- Unlocking the power of population health management to strengthen primary health care – ScienceDirect

- Virtual Wards Performance Evaluation & Re-Design – Akeso

- Health on the High Street – Akeso

- Left shift, right funds? The battle to move NHS money where it matters

- Darzi review sounds alarm over dwindling community nurse numbers | Nursing in Practice

- “Should it stay or should it go?” Making space for innovation: De-implementing old ways of working

- Allocative Efficiency, PHM, the Hewitt Review and You

- Stop adding, start cutting.

- The Hewitt Review: an independent review of integrated care systems – GOV.UK

- Bringing together people and analytics to make impactful changes – Health Economics Unit

- The Quest for Integrated Health and Social Care

- Digital Health and Inequity: Will Technology Close the Gap or Widen It? – Akeso